What's So Wrong With Identitylessness?

A tellingly compelling obsessive tendency of mankind is the search for identity, which, while typically and inextricably interchangeable with the ever-vexing search for meaning, is also an isolated enterprise that more often than not meaninglessly hinges on answering the "existential" query: who am I? Even though this question and its askers have ostensibly multiplied in today's world -- which could be explained away by the cultural resurgence of self-worship -- the quest for self-identification is a species-long one. The king to whom you've pledged most allegiance, the nation from which you hail, the race with which you share the most characteristics, the belief system with which you most agree, the surnames that signify vast heritages of individuals caught in the same struggle for survival and selfhood... these are the identifiers that so many people have died justifying in a meager effort and failure to apperceive the human predicament.

Why this is more disturbing than it initially appears to be is that the inconceivability of infinity or the unrelenting confrontation with mortality or the absurd but necessary belief in an omnipotent God or the endless oceanic inconsistency in which we consistently find ourselves thrashing to stay afloat are not digestibly reducible notions. And so due to our Darwinian drive for self-preservation in the face of such enormity, we either invent identity and engage in the Sisyphean endeavor to make reality small and sensible or we try to abandon identity by "letting go" of the ego (though, arguably, this usually becomes its own poststructuralist identity) and somehow blend with the infinite whole rather than recognizing the finite part, which is the self.

This is, particularly, that from which I am trying to distinguish identitylessness. As aforementioned, I don't mean, by this concept, the hippy-dippy, new-age egolessness -- the there-is-no-you-there-is-no-me-we-are-all-one-interconnected-cosmic-superconsciousness nonsense. No, I'm attempting to characterize something a bit more indeterminate. While there is a wishful and desirable universalism in "becoming" the whole, denying the reality of the individual ego is definitionally delusory. However, the modernistic individualism to which egolessness serves as a response is equally mistaken because it denies wholesale the existence of any interconnecting force, such as God or a collective unconscious. In order to accurately address reality, then, the individual ego must be contextualized amongst or against a vaster realistic understanding. This relational model in fact precisely defines the conceptual entities that comprise it. There is no singularity without an integrality from which to demarcate, and there is no whole without the parts that make it up.

To be clear, though, this still does not solve the identity crisis. To say "I am a part of the whole" is to say one is both the part and the whole, which is true in either case. But then one is neither distinguished from the part-whole paradigm, nor from any other parts. So in what way is it one's identity to characterize it as a part of a whole?

This crisis, as most would view it, is unacceptably insoluble to many. Identity is unmistakably a focal point in terms of social functionality and purpose-finding, and I'm baffled why this must be the case. An immortal mode of thought seems to necessitate identity and force those who comprise society to develop one. But, again, this is difficult to rationally justify.

Am I, for instance, the nationality of the country I was randomly born within? Well if I were born in a different country by happenstance, or even if the borders to that country were redrawn in the moment of my birth, would that fundamentally change who I am? If the rebuttal is that I'd speak a different language or wear a different style of clothing or eat different foods -- do these things comprise my being? The specific sounds I utter and the colors I wear and the comestibles that nourish me? If these aspects of a cultural tradition of a country came about by chance, arbitrary decisions, and as reactions to geographical and physical conditions, then why would I care to be defined by these things anyway? Are identities comprised of a series of random events? Am I my skin color? Well what about that determines who I am? Does my appearance elementally circumscribe my personhood? Do "my" people give me identity in my phenotypic and cultural associations with them? And if I am for whatever reason ostracized by that community does my identity dissipate? What is race? A collection of genetic output compiled by millennia of ancestors? If this does wholly and accurately encapsulate me, then relatives who chronologically precede me would possess less complex genetic data, and so do they have less identity than those who succeed them? If one suggested that the essence of identity is the synthesis of these things because they most pointedly specialize an individual, this still would not make one utterly unique. But even if this is dismissed, if identity is not necessarily defined by utter uniqueness, then these identities formed under this criteria are still manifestations of incidental phenomena, and hence would result in incoherent and meaningless self-conception.

There is nothing that comprises consequential identity other than the generic and mere ego, which fails axiomatically to uniquely individualize anyway. There is, however, a compelling suggestion of identity in things even more intangible. If I said "I am American," for instance, the meaninglessness of nationalism as articulated earlier applies. But if I said the moralism of the ideology of the nation from which I hail defines me, then I am proposing that immaterial ethics or some sort of spirituality does, just as if I said "I'm Christian" or, more generally, "I subscribe to dogmatic moralism." But this makes me more like a husk that harbors ideological actuality rather than a singularity possessive of substantive being.

If it was said that a church or a group of kindred believers defines individuality, then the aforementioned fallacy of association is pertinent here. But, once more, if moralities believed to be absolute, or, even more broadly, kinship with a deity, comprise identity then immateriality strangely but succinctly defines materiality and something as abstract as identity. Though, is this still a lack of unique identity since groups of individuals would claim to adhere to identical absolutes and an equal relationship with the divine? Well, ethical codes are ultimately personal, whether this in itself is ethical or not, because subjectivity is inevitably human. Everyone disagrees with aspects of dogmas (which is admittedly preferable since wholesale assent to a system of thought either results in fallacy or cult-reminiscence), which makes ethical perception and adherence rather unique. Or, if we each are in fact a child of God, we would be individually special to that omniscient understanding of personality. The soul, in other words, if it exists, would have to be the chief identifier of each person.

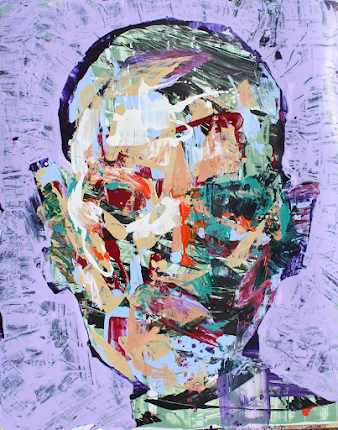

Nevertheless, if this is the case, then self-identification still rests in something indefinite, potentially infinite, and immaterial. Identity, moreover, cannot be defined because it lacks the very finitude to do it. A material definition of identity would have to be something much more corporeal. But even then, it would have to be an empty corporeality, such as a vessel. A mereological vagrant, in other words. A part of innumerable parts in space whose partial existence implicates a greater one of wholeness. A definable shell that houses something much less definable.

The basest and closest material descriptor of individuality would be the thing that abstractedly circumscribes soulful identity. Simply put, a dusty rind or a vacant house. More complicatedly, I suppose, an infinite part.

I don't think anybody cares who I am, and neither do I. But maybe an omnipotent God does.

Comments

Post a Comment